So, What's All the Fuss About Caviar?

Fish eggs, from sturgeon, salmon or other species, have been loved by many cultures. And now, they are more affordable!

Dec 18, 2023

Ask any random person in America what they know about caviar, and there's a good chance they'll identify it generically as fish eggs. Press them further and they'll likely tell you caviar comes from Russia, or at least the “good kind" does. Then they'll add that it's extremely expensive and mostly for the rich.

Some of that is correct, but much more of it is based on long-standing misconceptions that can be traced to caviar's turbulent 200-year history as an international commodity.

Entire books and at least one documentary have chronicled this fishy tale (pun intended). But the critical point about caviar is this: Forget what you think you know. Today, thanks to sustainable aquafarms like Tsar Nicoulai Caviar, even those of modest means can enjoy good quality caviar — one of nature's oldest and most unique delicacies.

When caviar is truly caviar

Caviar is, of course, unfertilized fish eggs or “roe" — but not just any kind. The official ruling among international governing agencies, including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), defines caviar strictly as the eggs of any of 27 existing species of female sturgeon whose home has been in the Caspian or Black seas, Europe's deeper lakes and rivers, the Pacific Northwest, or North America's South Atlantic regions for nearly 250 million years, making the big, boney fish contemporaries of dinosaurs.

Originally, the “caviar" designation was reserved for sturgeon eggs specifically from the Caspian Sea, which touches the shores of Russia and Persia (modern day Iran), or the Black Sea, which outlines parts of Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, Turkey, Bulgaria, and Romania. In particular, these seas were home to the Sevruga, Ossetra, and Beluga sturgeon. Their prized roe was considered of the highest quality, collectively.

But after reckless overfishing in those bodies of water wiped out nearly 90% of sturgeon by 1990, the designation was extended to include sturgeon roe from broader sea regions. It's important to note, however, that roe from female trout, steelhead, carp, whitefish, and salmon — which often tops sushi dishes and is deceptively marketed as caviar — does not qualify as such.

Caviar's not-so-humble beginnings

Human beings have harvested sturgeon roe or collected pools of sturgeon eggs along freshwater shorelines, historians tell us, for at least 4,400 years. The Egyptians and Phoenicians enjoyed caviar immensely. Likewise the Turks and Greeks, for whom, by the 2nd century BC, a single jar of caviar cost the steep price of 100 sheep. And in the 4th century BC, Aristotle wrote glowingly about trays of caviar adorned with flowers being carried through a banquet hall and announced by trumpets. (Seems like all the great entrances involve trumpets.) By the 8th century BC, Slavics and Russians were already pulling this “black gold" from the Caspian and Black seas at a record pace.

Ancient Persians — not surprisingly, given their proximity to the Caspian Sea — were responsible for developing the critical process of “curing" the roe and essentially turning it into caviar. The recipe has remained virtually unchanged over the centuries and includes sorting, rinsing, salting, draining, and carefully blotting dry the eggs by hand to keep the pearly shapes intact.

Persians, according to linguists, also named the delicacy. The word "caviar" comes from the Persian “khavyar," which means “cake of strength," a reference to their people's belief that sturgeon roe contained powerful medicinal properties. They were correct, although how they knew is anybody's guess. Caviar is rich in proteins, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin B12, and selenium, a mineral that's critical to human reproduction, metabolism, DNA synthesis, and protection from oxidative damage and infection.

From Russia, with no love for Persia

It may have vexed Persians that although they essentially put caviar on the map, Russia was almost immediately the place most associated with the briny delicacy, and still is. Much of that is due to the legendary and prolific fishing skills of Russian seamen, but more of it has to do with Russian tsars who, beginning in the 1200s, promptly declared caviar an “imperial" food. Sure, they were wild about its unique flavors, but they also greatly romanticized its exotic nature. That's because while sturgeon may have been easy to catch, the males have always been hard to tell from the females, and latter require at least eight to 10 years before they mature and produce eggs.

All that creates yield problems — what economists refer to as “scarcity," or “exclusivity," which is irresistible to the hyper-entitled set. So it was only natural when European royalty, including King Edward II of England, followed Russian braggadocios, designating caviar a “royal" food, barring it from their subjects, and declaring imported Russian caviar to be of the highest and most aspirational quality.

Ikura: "Caviar" from salmon

The allure of fish eggs extends to other species, and other cultures, as well.

You’ve seen those glistening red globes wrapped in seaweed on a sushi platter?

Theyse are unfertilized eggs harvested from salmon, a rich and much-prized delicacy, and an excellent source of calcium, vitamin A, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids.

As noted above, salmon eggs are not technically caviar, but biologically, fish eggs are fish eggs!

The Japanese call them ikura when they are freed from a connecting membrane and are separated into individual eggs. The word comes from the Russian ikra, meaning fish eggs. When left in a cluster within the membrane, they are called sujiko.

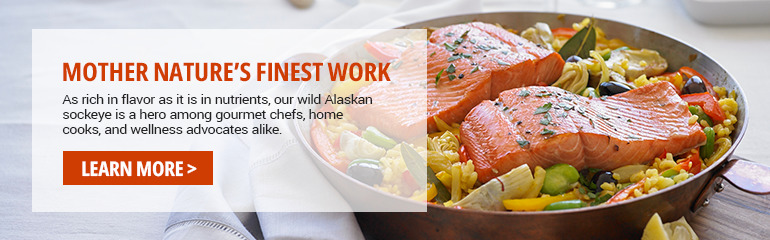

Salmon roe can be frozen, crushed, mixed into pastes and spreads, or dried. But it’s most delicious at its simplest, whole and brined — using quality salmon, which in our case means wild Alaskan keta, sockeye, and pink salmon.

Keta roe tends to be the most popular, offering the signature “pop” in the mouth preferred by ikura aficionados.

How to serve and eat the best caviar for beginners

Caviar is most often served alone and in portions equivalent to a half teaspoon. Enthusiasts have strong feelings about using special mother-of-pearl spoons because metal can alter the taste. They also insist on pairing caviar with chilled Champagne, sparking wine or, more traditionally, top-shelf Russian vodkas.

Just as with wine tasting, caviar is characterized first as having a base flavor profile that can be muted, full, or briny, followed by additional buttery or nutty notes with finishes that range from creamy to clean. For this reason, and especially when served on its own, caviar is not meant to be chewed. Savor it on the tongue, and then move it around the mouth before swallowing.

Caviar is traditionally presented as an hors d'oeuvre, piled on a blini (a small Russian pancake made from buckwheat flour), and topped with a bit of crème fraiche and sometimes even bits of hard-boiled egg or chopped scallions. Unsalted crackers and toast points are also used as a base.

But these days an increasing number of imaginative chefs are bucking hard tradition and doubling down on seafood combinations, pairing caviar with oysters or using it to highlight entrées of scallops or lobster over angel hair pasta or risotto.

In short, the days of "caviar" being defined as the wealthy eating sturgeon eggs with bone spoons are over. Enjoy the new, egalitarian age of creative caviar consumption!