Sockeye Salmon Facts: America’s Iconic Wild Fish

Sockeye salmon comes with a fascinating history as well as delicious flavor.

Nov 22, 2022

In Alaska, wild sockeye salmon are one of the most iconic, and important, salmon species. They offer sustenance to humans and form a key part of the ecosystem.

For thousands of years, the massive annual sockeye salmon migrations have provided ample food for people in the region, who rely on the fish for protein during long, cold winters. Today, wild Alaskan sockeye salmon form the backbone of a thriving sustainable fishing industry.

The throughline from the past to the present is a recognition of wild-caught Alaskan sockeye salmon as a delicious food filled with protein and vital fats, plus other nutrients our bodies need. Alaskan fishermen regularly pull millions of sockeye from Bristol Bay and other watersheds along the coast. Yet they also ensure that enough make it through to keep populations strong. And indigenous fishers make use of ancestral techniques to catch sockeye salmon, as their ancestors have for millennia.

In short, it's no exaggeration to regard the sockeye as the most important American wild fish. With that in mind, let's learn more:

Sockeye salmon facts and history

Wild Alaskan sockeye salmon, or Oncorhynchus nerka, are a species of wild salmon that live in the northern Pacific. They can be found anywhere from northern Oregon to above the Arctic Circle in Alaska. Their range extends west to Japan and Siberia.

Adult sockeye salmon size reaches up to almost three feet in length. They can weigh anywhere from five to 15 pounds. The name “sockeye" is an English adaptation of suk-kegh, a name that means “red fish" in the indigenous language Halkomelem, spoken by the First Nations people of what's now British Columbia.

The name red fish is quite appropriate because, while sockeye salmon are blue and silver in the ocean, their bodies turn bright red when they return to their freshwater spawning grounds. Like other anadromous (living in both salt and freshwater) salmon species, sockeye make long migrations from the ocean back up the rivers they were born in to mate.

When that happens, their bodies undergo startling changes. In addition to turning red, sockeye also grow hooked jaws that help them fight for mates.

Scientists think salmon imprint on the molecular signature of their home streams, which allows them to “smell" their way home again. Once in the quiet pools and gentle streams they were born in, female sockeye make redds — small nests in the gravel streambed — and deposit thousands of eggs for males to fertilize.

Come spring, these eggs will hatch into “alevins," who turn into juvenile fry and eventually adult salmon, who make their way to ocean hunting grounds where food is plentiful. Adult sockeye spend several years in the ocean, eating a diet composed chiefly of krill, before returning to their rivers to start the cycle anew.

A sacred tradition of Alaskan sockeye salmon fishing

Sockeye salmon have represented the life-giving bounty of nature for indigenous people for thousands of years. For tribes along the Pacific Coast from Oregon to Alaska, the return of the sockeye salmon migration in fall is cause for celebration, and an annual hunt that provides food for the long winter while respecting salmon populations. Sockeye salmon caught during the harvest would often be smoked or dried for preservation, and eaten all winter long.

There is evidence of wild salmon fishing in Alaska dating back to prehistoric times. Stone pools and weirs, or barriers, for corralling and capturing salmon that are nearly 4,000 years old have been found on Alaska's Prince of Wales Island. These techniques are still used today by tribe members.

In some tribal traditions, salmon offered themselves as food for humans in a time of starvation, symbolized by their annual return. Many tribes also see the salmon as spiritual equals to humans, and treat them accordingly. Though indigenous Alaskans depended on salmon for food, they had sophisticated systems for ensuring that enough salmon survived every year to keep populations healthy.

A path to commercial salmon fishing

Today, the wild Alaskan sockeye salmon harvest is one of the most sustainable in the world. It draws on salmon populations that have remained healthy for decades. Strong partnerships between scientists, policymakers and fishermen ensure catches adhere to quotas and that salmon numbers remain high.

But it wasn't always that way. In the middle of the 20th century, Alaskan salmon numbers dipped dangerously low, due to overfishing and poor management. It was only after Alaska gained statehood in 1959 and began managing salmon populations itself that their populations began to recover.

The history of commercial sockeye salmon fishing in Alaska dates back well over a century. The first salmon cannery opened in the territory in 1869, and by 1920, 160 canneries operated there. The annual salmon harvest jumped from 30 million in 1910 to more than 60 million by 1920, and peaked at around 90 million salmon in the 1930s. But those numbers declined to just 25 million by 1959.

That year, the new Alaskan state Constitution explicitly called for sustainable management of fish populations, marking a shift in the way salmon and other species were treated. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, and continuing to today, the Board of Fisheries and the Alaska Department of Fish & Game oversaw fishing operations, collaborating with scientists to monitor the health of salmon populations and set quotas for catches.

That oversight has ensured a healthy supply of sockeye salmon every year, and a reliable bounty for seafood lovers across the country. Catches in Bristol Bay, where much of Alaska's sockeye salmon return on their way upstream to spawn regularly top 50 million fish. And in 2022, the Bristol Bay salmon catch numbered around 75 million sockeye, setting a new record. In the fishing district of Nushagak, fishermen hauled aboard 2 million sockeye in one day alone in July.

Alaskan fishermen use more sustainable fishing techniques like purse seines and gillnets that reduce bycatch and environmental damage. And offshore net pens for salmon farming are illegal in Alaska, meaning that every fish that comes from Alaska is wild-caught.

Wild sockeye salmon nutrition facts

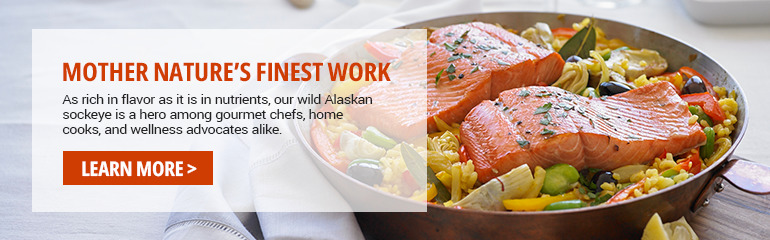

Though all salmon are great options for nutritious meals, sockeye salmon facts indicate it can be a particularly great choice. They have higher levels of the omega-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA than almost any food. They also offer high levels of the antioxidant astaxanthin (which also gives their meat a rich pink color).

Our bodies can't make enough omega-3s on their own, meaning we need to rely on our diet — and especially seafood — to get enough. The American Heart Association recommends eating one to two servings of seafood per week to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Wild-caught sockeye salmon also offer vitamin D, iron, selenium and lean protein. A single three-ounce serving of sockeye salmon has 22 grams of protein, beating out many other foods. Wild sockeye salmon are rich, tender and delicious enough to make for a mouth-watering meal any time. Find skinless wild sockeye salmon filets on Vital Choice, in either four or six ounce portions.