Eat Like a Medieval

These medieval food facts will take you back to the days of fish, hearty stews...and no forks!

Oct 22, 2022

When we foodies travel, we often come home with new tastes and a fresh appetite for culinary adventure.

Traveling in time can be even more eye-opening.

Eating and cooking in medieval England and Europe looked a bit like the recommendations you'll read in 2022 health blogs. Those "whole, unprocessed foods" we now celebrate are, in fact, the preindustrial diet.

Ironically, as I described in "Eat Like a Mid-Victorian," even some people of modest means in earlier eras ate better than many of today's fast-food consumers.

So let's take a look at what was on the menu during the Middle Ages, roughly between A.D. 500 and A.D. 1400.

Medieval food? Fish, forsooth!

In an homage to Noah's ark, ordinary people in medieval Cumbria, a county in northern England, would not slaughter God's creatures four days a week. But they could eat fish on meatless days in the Catholic calendar (see "Why Do People Eat Fish on Fridays?"). And strangely, because beaver tails looked a bit fishlike, beaver was okay too, notes a well-researched cookbook about the county — Medieval Meals: Cook & Eat in the 12th Century.

Cumbria, then part of Scotland, was protected from the chaos of the bloody civil war, and the book shows that its peasants fared surprisingly well. They enjoyed a diet we can admire today: low in sugar and rich in whole grains, local vegetables, fruit, and fish. They used large fishing nets for their catch and cooked over open fires with spits or suspended pots.

Across medieval Europe, people fasted regularly, used almond milk, and ate thick breads. Monks in particular ate huge portions of beans. Doesn't this sound like our food coop fare, but without the packaged "healthy" snacks?

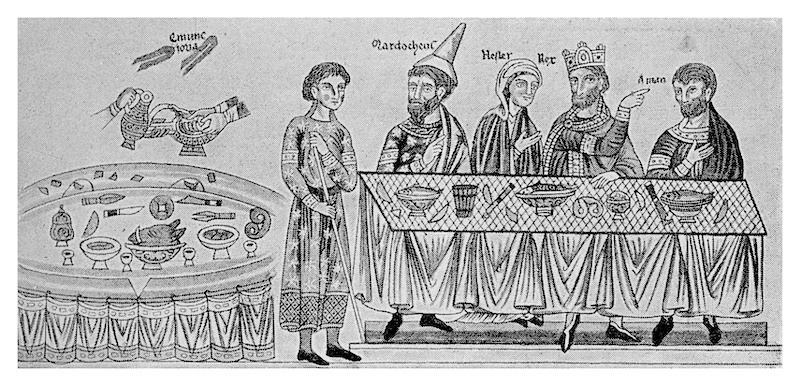

Use a spoon, or your hands

Some customs aren't so familiar, though. Medievals cooked all vegetables and ate stews by picking up morsels with their hands or using communal spoons in a central serving dish (forks weren't in general use in Britain until the 1700s).

Many recipes of the time allowed cooks to swap in whatever protein was available: beef, pork, fish, or fowl.

The British Museum offers a modified 1400s (considered the Late Middle Ages) recipe for civet stew from The Medieval Cookbook. It calls for haddock, filleted and cut in pieces so it can be eaten without a fork, cooked with onions, white pepper, bread crumbs, and brown ale.

The wealthy might add costly saffron. Or, as was written at the time:

Shal be yopened & ywasshe clene & ysode & yrosted on a gridel; grind peper & saffron, bred and ale mynce oynons, fri hem in ale, and do therto, and salt: boille hit, do thyn haddok in plateres, and the ciuey aboue, and ghif forth.

Ancient almond milk

Mortrews was a type of stew using almond milk that could be thickened into pâté with rice or corn flour (dairy- and gluten-free way back when!).

A French cookbook from around 1400 suggested using chicken liver for the thickener except on the many days when meat was forbidden on the Catholic calendar. In the British Museum update you'll make your own almond milk and mix it with poached flaked cod in an electric blender.

Presentation is important: The recipe calls for plating each serving with a portion of the pâté that you've colored gold using ginger, saffron, or food coloring and a portion that is white. Both are sweetened with sugar, which was a great luxury for the upper crust of the time.

In other words:

To make mortreux of fisch. Tak plays or fresch meluel or merlyng & seth it in fayre water, and then tak awey the skyn & the bones & presse the fisch in a cloth & bray it in a mortere, and tempre it vp with almond melk, & bray poudere of gynger & sugre togedere & departe the mortreux on tweyne in two pottes & coloure that on with saffroun & dresch it in disches, half of that on & half of that other, & strawe poudere of gyngere & sugre on that on & clene sugre on that other & serue it forth.

And true to form, medieval desserts were more likely to rely on fruit than on sugar — for the more fortunate, that meant using exotic berries, citrus fruits, and spices brought from the Middle East by returning Crusaders.

Reading these recipes might just inspire you, like the heroine of Outlander, to take a quick trip and find your true love in another century.

And if, by chance, you land in a medieval kitchen, you'll be all prepared to cook your new true love a hearty supper.