Which Country Eats the Most Seafood?

The people here eat four times as much as Americans consume. What can they teach us?

Mar 08, 2023

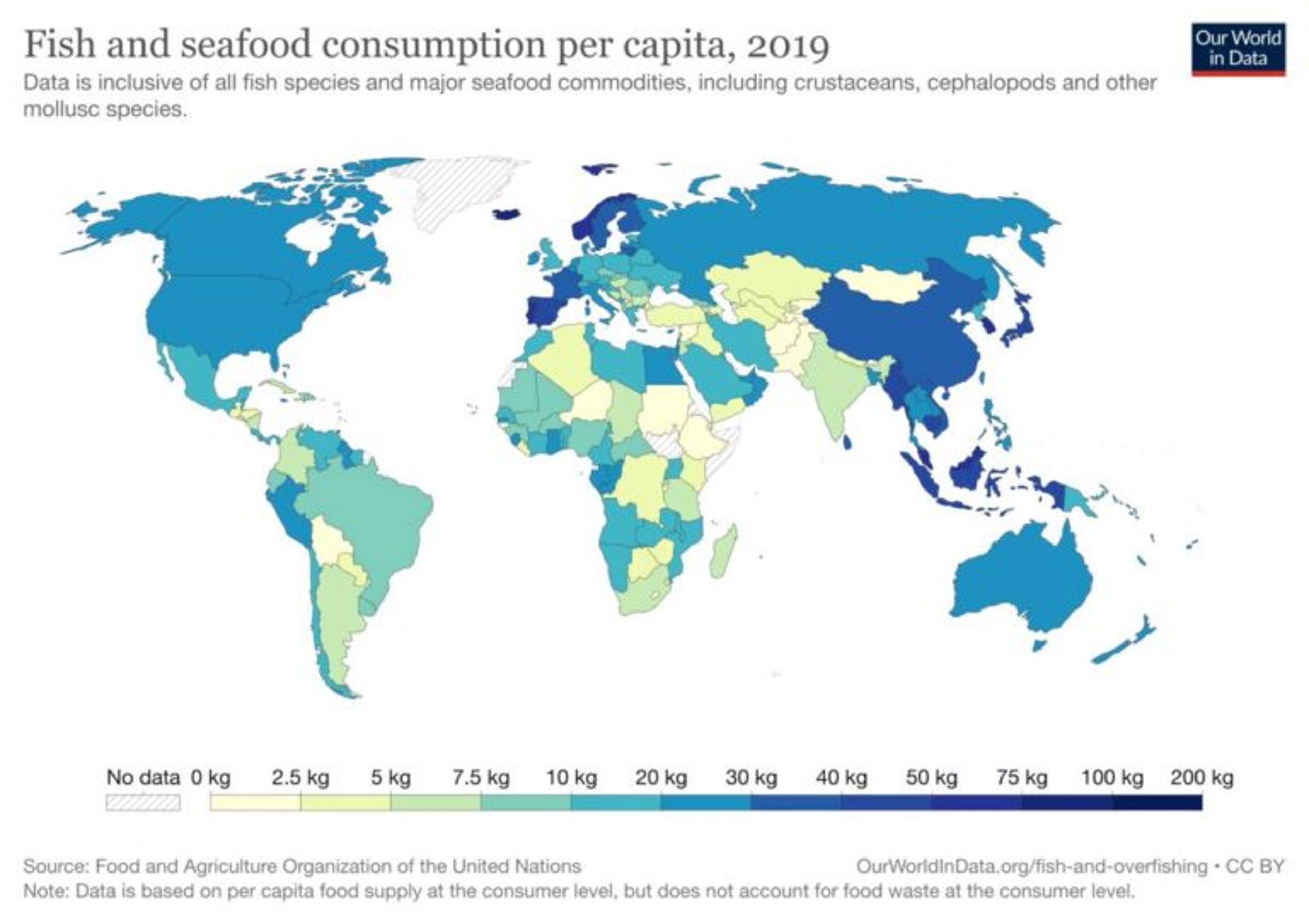

Seafood is popular worldwide. But which country truly claims the fish-loving crown? A new chart from the World Economic Forum has the answer: Iceland.

The people of Iceland easily consume the most seafood per capita, beating out other coastal nations like Portugal, Japan and South Korea.

The average Icelander eats just over 200 pounds of seafood a year. That's more than a half pound of seafood every single day.

The United States sits relatively far back in the rankings, at 49 pounds of seafood annually per capita, just above the fish-and-chips-loving United Kingdom and just below Australia.

By contrast, the average Icelander eats more than four times the global average of 45 pounds of seafood per person every year. In fact, the tiny nation has been one of the top seafood-consumers for decades, according to data from the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United States.

How does the small island country, known for its volcanoes and geothermal energy, do it? One big factor is a long history of fishing, and a reliance on the sea for sustenance. A harsh climate, short growing, and rocky soils made farming a challenge, so Icelanders have naturally looked to the sea for survival ever since the island was settled in the 9th century. Fishermen chased cod, haddock and other cold-water fish during seasonal migrations that began off the island's south shore and moved up the western coast.

Suppose you are an American seafood lover. Can you learn from Iceland's fish-centric food culture? Read on.

History of Icelandic fishing

The 18th century brought a novel form of propulsion in the form of sails, which allowed Iceland's fishing industry to expand and begin exporting more products to Europe. Salted cod and shark liver oil for street lamps were two main exports during this time.

The fishing industry expanded again following the introduction of motorized vessels in the early 20th century and, following hard times during the Great Depression, bounced back during and immediately after the Second World War with a modernized fleet and larger vessels.

The second half of the 20th century saw Iceland begin expanding its sovereign waters, a move that angered fishermen in the United Kingdom who had been ranging far from their home waters in search of new catches. The resulting dust-up, called the Cod Wars, saw tense standoffs between the Icelandic Coast Guard and British naval vessels, and several boat-ramming incidents.

Today, fishing remains an important part of the Icelandic economy, even as it's expanded far beyond its roots. Despite its tiny size and relatively small population, Iceland is the seventh-largest exporter of fish filets in the world. That includes some of Vital Choice's Wild Atlantic Haddock, which is wild-caught and flash frozen within hours of catch. Try some today and see if you can tell why Icelanders love their seafood so much!

Cook fish like the Icelandic pros

Any country whose residents consume 200 pounds of seafood each per year must know a thing or two about seafood. So, it stands to reason that adding a little Icelandic flair to your cooking might be a great way to liven up your next seafood dinner.

For an Icelandic spin on a fish dinner, try making a Plokkfiskur, or fish stew. Despite the unfamiliar name, this dish is super easy to prepare: Boil a white fish like cod or herring and potatoes, and mash them together, then add a simple béchamel sauce made from flour, milk and butter. Or go with the equally popular Icelandic dish of fish soup, which can be modified in a number of ways, but starts with potatoes, leeks and white fish.

For a more solid meal, consider Fiskibollur, which are similar to croquettes. Mix fish, onion, flour and eggs in a food processor, and then form into balls and fry in butter for a hot, lightly crispy hand-held delicacy that's super savory. Or put an Icelandic spin on British fish and chips by using spelt flour and frying with rape-seed oil for a lighter texture, and serve with roasted, not fried, potatoes.

Then again, if you really want to experience seafood as the Icelanders of olden times did, there's no better option than Harðfiskur. This traditional drying process involves hanging white fish like cod or haddock outside for several weeks, sometimes after soaking it in a weak brine. The fish are tough, chewy and salty, and are often eaten with a generous lump of butter on top.

No matter if you're looking for a new way to serve classic white fish, Icelandic cuisine offers an array of time-tested options for hearty, wholesome seafood meals. Take it from the people who eat 200 pounds of seafood a year — they must be doing something right!

One of the most popular seafood dishes in Iceland is "Plokkfiskur," which is a creamy fish and potato stew. It's similar to our familiar American fish/clam chowders except that the potatoes are left whole, rather than diced.

Here's a recipe for making Plokkfiskur at home:

- 1 pound white fish fillets (such as cod or haddock)

- 1 pound potatoes, peeled and diced into small pieces

- 1 large onion, chopped

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour

- 2 cups whole milk

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 14 teaspoon black pepper

- 14 teaspoon ground nutmeg

- 14 cup chopped fresh parsley

- Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C).

- Boil the potatoes in salted water for about 10 minutes, or until tender. Drain and set aside.

- Meanwhile, in a large skillet, sauté the onion in butter over medium heat until soft and translucent.

- Add the flour to the skillet and stir until well combined.

- Slowly pour in the milk, whisking constantly, until the mixture is smooth.

- Add the salt, black pepper, and nutmeg to the skillet and stir well.

- Add the fish fillets to the skillet and cook for about 5 minutes, or until the fish is cooked through and flakes easily with a fork.

- Add the cooked potatoes to the skillet and stir gently to combine with the fish and sauce.

- Transfer the mixture to a baking dish and bake for 10-15 minutes, or until the top is lightly browned and crispy.

- Sprinkle the chopped parsley over the top of the Plokkfiskur and serve hot with a side of dark rye bread.