Eat fish… and beans, eat local, plant your own vegetable garden, avoid waste, cut back on fat, and eat fruit for dessert. Doesn’t that sound like cutting-edge dietary advice?

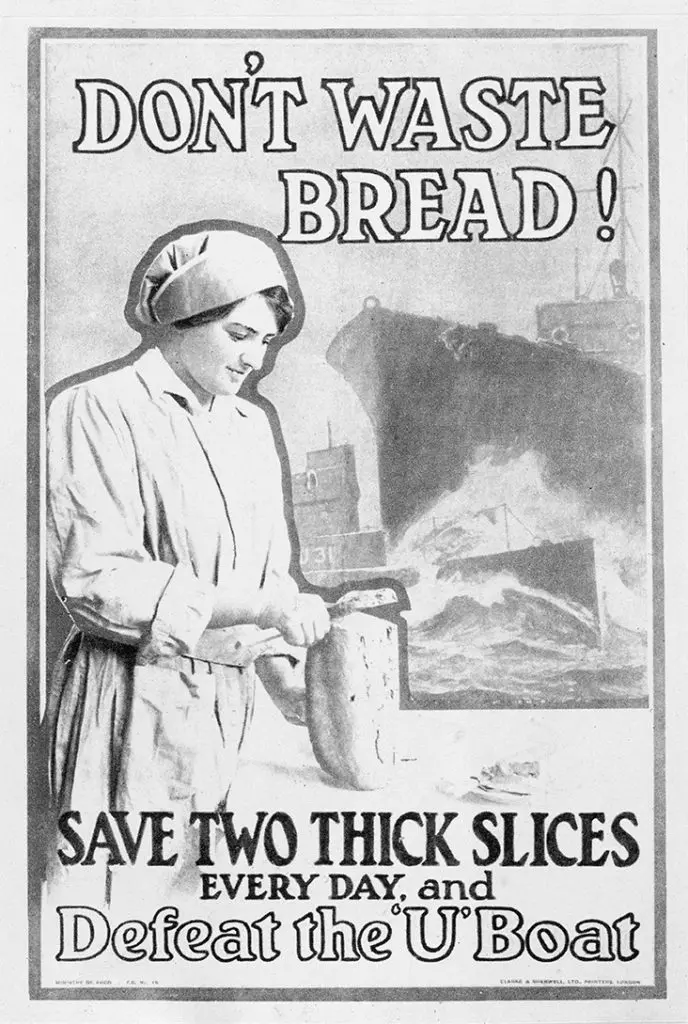

Look at posters and recipes from World War I, and you’ll see that Americans heard, and to a great extent responded, to this advice more than a hundred years ago.

And in World War II in the early 1940s, Americans again ate like patriots when fresh seafood became scarce, while our fishing boats and crews focused on military duties.

Diet for World War I

The United States Food Administration, created in 1917 under President Woodrow Wilson, launched a campaign to conserve food needed overseas in wartime. Led by Herbert Hoover, who would later become President, the new agency asked civilians to step up in a very personal way, by changing how they ate.

Colorful posters reminded Americans what was at stake, and inserts in newspapers and magazines provided recipes. On the new “Meatless Mondays,” patriotic Americans ate fish, beans, and nuts, alongside vegetables from their “victory gardens,” while sending prayers to the troops and starving civilians in Europe.

The idea wasn’t that meat was bad for you, but rather that it needed to be sent abroad. America lacked the fish-centric culture of Asia and parts of Europe, but the aim was to feed more people with the resources at hand, and that meant more fish on dinner plates.

Also, children cut back or gave up candy. Prewar Americans had a big sweet tooth; we ate more than twice the sugar per person than the British and four times the German consumption. The government asked cooks to stop frosting cakes, put less sugar in coffee and serve desserts like apple Brown Betty that relied on fruit, with corn syrup or honey for sweetener.

The United States School Garden Army nudged children to plant their own vegetables; community gardens appeared; and more women learned to can and preserve home-grown fruit, beans and corn. “War bread” might contain rice, barley, rye, oats, or buckwheat, so that wheat could be saved for other uses.

The campaign succeeded: Food shipments to Europe doubled within a year, and after the war, Americans continued to ship food to millions of people starving in central Europe.

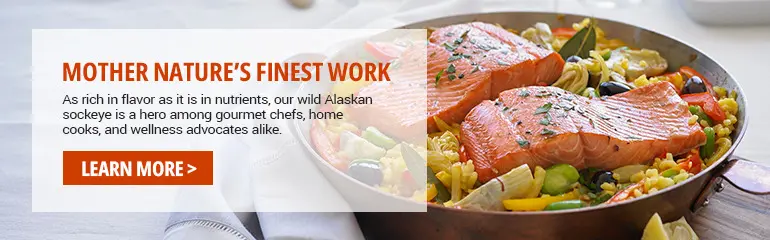

Promoting seafood in wartime was central to the project

Working closely with the Pacific seafood industry, the government promoted mackerel, herring, grayfish and sablefish, and discouraged the sale of fresh salmon, so that it could be canned and shipped overseas. The government became a guaranteed market for salmon, which encouraged new canneries. Herring canneries boomed as well.

In Great Britain, the Win-the-War Cookery Book, published in 1918 as part of the country’s own food economy, offered protein-stretching innovations like fish sausages that combined cooked white fish with rice, herbs, egg and oatmeal.

Fish and chips, the British staple, were not on ration, as the nation’s leaders understood that the popular dish was too symbolic to officially limit. But it was hard to get. The British waited long hours on line when the sign “Frying Tonight” appeared in a shop window.

Diet for World War II

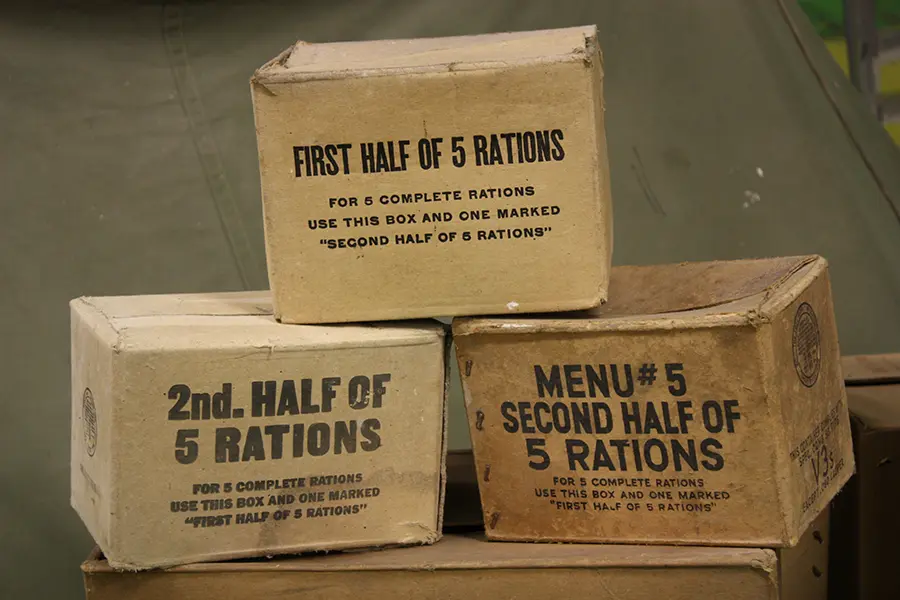

In the second great war, the U.S. food efforts turned to mandatory rationing. By the spring of 1942, Americans needed a coupon to buy sugar. Vouchers for coffee came that fall, and vouchers for meat, cheese, fats, canned fish, and canned milk arrived by March 1943. A barter system sprang up with people trading stamps, alongside rare black markets that forged stamps or sold stolen food.

Fresh fish became less available because boats were put to other uses. In fact, across the Atlantic, there was an unexpected benefit in the North Sea: a six-year pause in commercial fishing allowed the over-fished population of cod, haddock and whiting to recover. Facing mines and submarines, fishing captains found the North Sea too dangerous, and manpower scarce.

Fishing boats played a key role in the war. Some 850 “little ships of Dunkirk,” consisting of recreational, commercial and fishing boats, would sail from England to Dunkirk, France, to evacuate more than 300,000 Allied troops, ferrying them to destroyers further offshore or bringing them home.

When the United States entered the war a year and a half later, it asked the Alaskan seafood industry to step up, using vessels for transportation, minesweeping, and other military tasks. Government controls ensured enough canned sardines for the military.

Possibly because Americans appreciated that fish and shellfish were no longer scarce post-war, consumption rose steadily in the late 1950s.

Lessons learned from seafood in wartime

This history suggests that if war, or another situation as dire, should arise, citizens can respond. Americans have cut back on sugar, grown their own vegetables and upped, or adjusted, their seafood consumption before.

And the next time you enjoy a can of canned salmon, perhaps you’ll remember that this is a food that helped feed our troops, and in its own modest way contributed to the world we appreciate today.